The workhorse of all data science work is the basic linear regression model. It has the capability to change the direction of a business like a rudder on a boat but like a rudder, it is often overlooked by most practicioners until other more ‘advanced’ tactics are tried.

Here is an example of a basic bayesian linear regression model in R and stan.

Simulating the data is pretty straight forward.

set.seed (123 )<- 100 <- rnorm (N, 0 , 1 )<- 2.5 <- 0.8 <- 1.0 <- alpha_true + beta_true * x + rnorm (N, 0 , sigma_true)<- data.frame (x, y)head (df)

x y

1 -0.56047565 1.341213

2 -0.23017749 2.572742

3 1.55870831 3.500275

4 0.07050839 2.208864

5 0.12928774 1.651812

6 1.71506499 3.827024

Now that we have the data we want to create a linear regression model that shows the results of

<- lm (y ~ x, data = df)summary (lm_fit)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x, data = df)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.9073 -0.6835 -0.0875 0.5806 3.2904

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 2.39720 0.09755 24.574 < 2e-16 ***

x 0.74753 0.10688 6.994 3.3e-10 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.9707 on 98 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.333, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3262

F-statistic: 48.92 on 1 and 98 DF, p-value: 3.304e-10

Key parts of summary(lm_fit):

Estimate: point estimates of intercept and slope

Std. Error: estimated standard error of each coefficient

t value, Pr(>|t|): classical hypothesis test for each coefficient

Residual standard error: estimate of σ

Multiple R-squared: variance explained

2.5 % 97.5 %

(Intercept) 2.2036098 2.5907841

x 0.5354312 0.9596255

Interpretation (frequentist):

If we repeated this estimation procedure infinitely many times, 95% of the constructed intervals would contain the true parameter.

(Contrast: in Bayesian, you’d say “there’s a 95% probability the parameter lies in this interval, given data + priors.”)

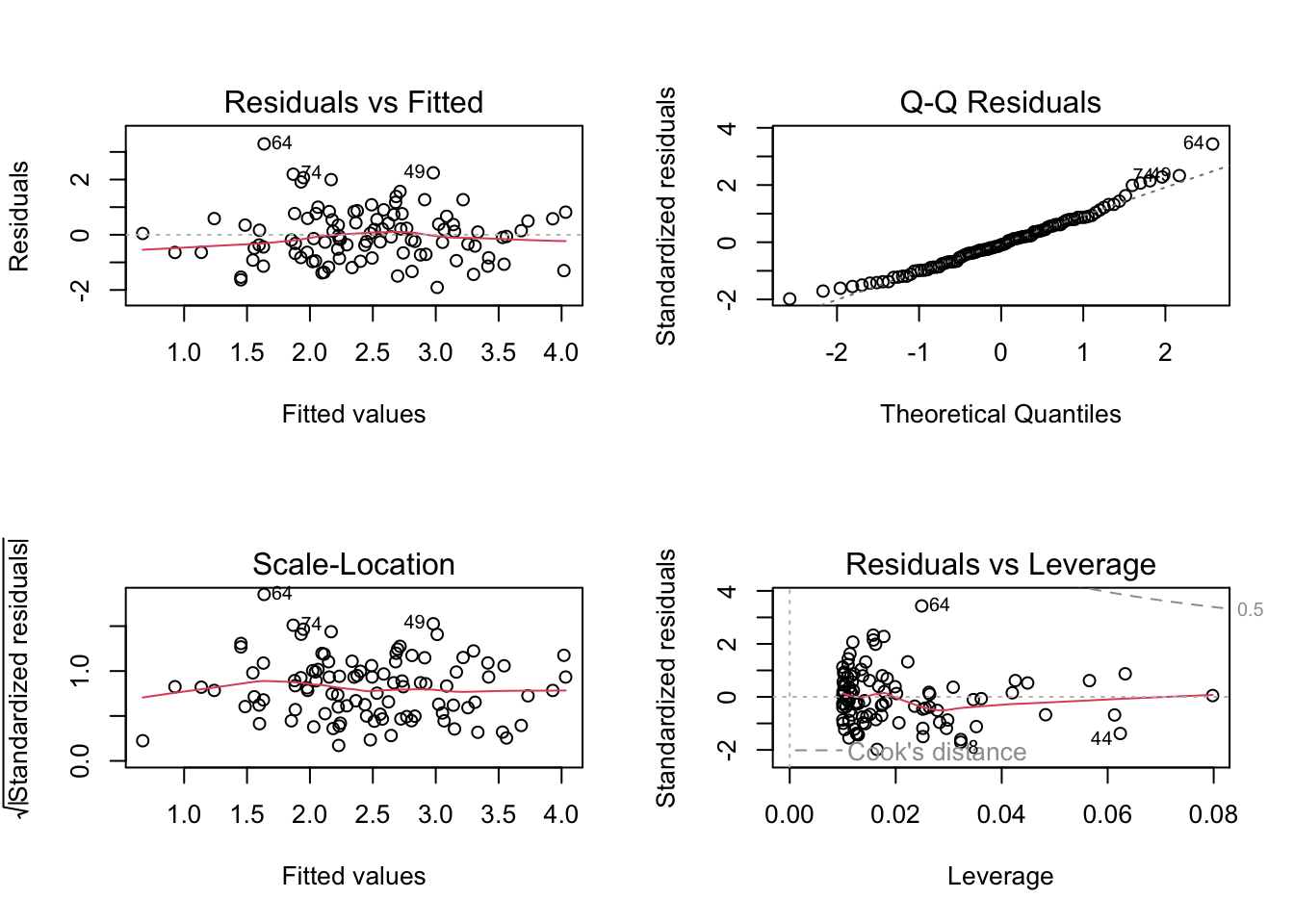

Basic Diagnostic Plots

par (mfrow = c (2 , 2 ))plot (lm_fit)

You get:

Residuals vs Fitted (linearity, homoskedasticity)

Normal Q-Q (normality of residuals)

Scale-Location

Residuals vs Leverage (influence)

Predictions with confidence & prediction intervals

<- data.frame (x = seq (- 2 , 2 , length.out = 30 ))# Confidence interval for the *mean* response <- predict (lm_fit, newdata = new, interval = "confidence" , level = 0.95 )# Prediction interval for a *new* observation <- predict (lm_fit, newdata = new, interval = "prediction" , level = 0.95 )head (pred_conf)

fit lwr upr

1 0.9021402 0.4187310 1.385549

2 1.0052475 0.5485212 1.461974

3 1.1083549 0.6779769 1.538733

4 1.2114623 0.8070330 1.615892

5 1.3145696 0.9356071 1.693532

6 1.4176770 1.0635953 1.771759

fit lwr upr

1 0.9021402 -1.0839403 2.888221

2 1.0052475 -0.9745075 2.985003

3 1.1083549 -0.8654881 3.082198

4 1.2114623 -0.7568858 3.179810

5 1.3145696 -0.6487041 3.277843

6 1.4176770 -0.5409462 3.376300

“confidence” = uncertainty about E[y | x]

“prediction” = uncertainty about a new y at that x (includes residual noise, so wider)

library (ggplot2)<- cbind (new, as.data.frame (pred_conf))names (pred_df) <- c ("x" , "fit" , "lwr" , "upr" )# ggplot(df, aes(x, y)) + # geom_point(alpha = 0.7) + # geom_line(data = pred_df, aes(x, fit)) + # geom_ribbon( # data = pred_df, # aes(x = x, ymin = lwr, ymax = upr), # alpha = 0.2 # ) + # labs( # title = "Frequentist Linear Regression (lm)", # subtitle = "Fitted line with 95% confidence band for mean response" # )

Quick contrast with your Bayesian version Using the same simulated data:

Frequentist (lm):

Coefficients: point estimates + SE

95% CIs: coverage interpretation over repeated samples

p-values: H₀ tests (β = 0, etc.)

Bayesian (stan_glm):

Coefficients: full posterior distributions

95% intervals: “credible intervals” (probability statements given model + priors)

No p-values; you might instead look at Pr(β > 0) or posterior density.